Dadaism is the inspiration for an exhibition exploring its links with art from African contexts at the Berlinische Galerie in Berlin

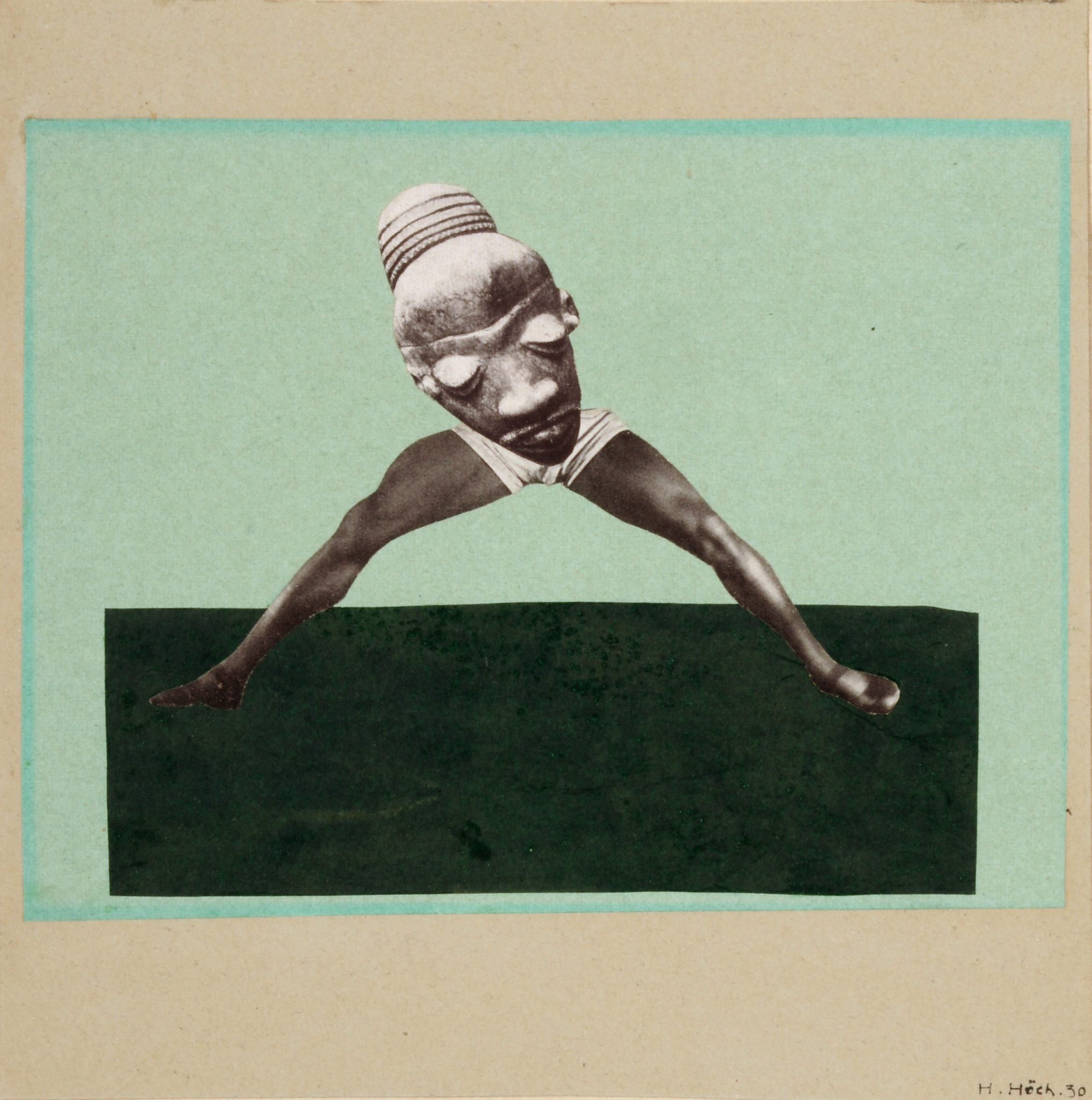

Hannah Höch, Untitled, from an ethnological museum. Collage. Courtesy of the Berlinische Galerie

So far, the issue of Dadaism and Africa has been ignored by the European public, although in the media it has been stylized as a “new discovery”. The exhibition’s title, however, DADA Afrika – Dialog mit dem Fremden (DADA Africa – dialogue with the other) signifies a conservative approach and that Dadaists were far from recognizing European and African cultures as equal.

The exhibition is the result of an unusual collaboration between two museums with distinctly different focus areas: the ethnological Museum Rietberg in Zurich, where the exhibition was first shown, and Berlinische Galerie, specializing on art from Berlin since 1880. The occasion for this collaboration is the centenary of DADA. Zurich and Berlin were the centers of this movement.

The Berlinische Galerie has an extensive collection of DADA artworks, in particular by Hannah Höch. The Rietberg Museum can establish a connection to DADA on account of two significant collectors: Eduard von der Heydt, whose collection of non-European art inspired several DADA artists and became the museum’s foundation collection; as well as Han Coray, who opened the first DADA gallery in Zurich and exhibited DADA art in tandem with African art.

.

.

With this as its basis, the DADA Afrika exhibition sheds light on an aspect of the creative practice of many DADA artists that has so far been largely ignored: their fascination with non-European art. Many DADA collages are praised by art historians for their technique and their radical messages. However, the use of images of African masks is at best a marginal note and has as yet not been researched in detail. Especially in the exhibition catalogue, significant research findings regarding the provenance of the images used are cited, providing insights into the reception of African art in Central Europe in the early 20th century.

The onomatopoetic poems by Richard Huelsenbeck and Tristan Tzara also have a link to the African continent. “Umba”, called out as a seemingly meaningless word fragment between verses, was a popular joke among audiences. In actual fact, Umba is the name of a river forming the border between Kenya and Tanzania, where at the beginning of World War I, colonial troops from Britain and the German Reich stood facing one another. Did the audience in Zurich know this at the time? Today at least barely an art historian has this knowledge.

By using African words and masks taken out of their original context, the DADA artists wanted to provoke. But – and in this they were following a long-standing tradition – they also wanted to hold a mirror up to the Europeans. Countering Europe’s degenerateness, Africa served as the pure, ideal and original antithesis. They did not bother to acquaint themselves with African realities.

Ultimately, the DADA artists drew on the same stereotypes as the colonialists did. On the one hand masks could be used to instill fear, on the other they could refer to a better – because more original – world; and the Africans’ alleged lack of history could be interpreted in any way one pleased. The DADA artists did this without restraint.

Regarding this in a critical light today, one would justifiably have to reproach the DADA artists for the way they dealt with African cultures. However, in the exhibition and in several essays in the catalogue, it is alleged that DADA appreciated African art and regarded it as potentially equal. Although this is a possible interpretation, this assumption evokes a feeling of unease.

With its glass cabinets and framed pictures, the exhibition itself does not exude any sort of DADA atmosphere, displaying DADA art and African artifacts alongside each other without descriptions. This is supposed to emphasize the equal value of the art – which only works to a limited extent. Ultimately it only shows the African artifacts the DADA artists used for their work. And the categorization into different DADA chapters, for example “DADA Magie” (DADA magic), seems rather questionable.

.

Installation view Dada Afrika – Dialog mit dem Fremden, 2016, Berlinische Galerie, Berlin. Courtesy of the Berlinische Galerie

.

DADA Afrika reveals a conservative exhibition policy, presenting the context of European art and Africa as a one-way street. At most, African artists are attributed the passive role of suppliers of artifacts.

But there are other ways, as the exhibition Dada South at Iziko National Gallery in Cape Town (2009/10) demonstrated. In their noteworthy essay in the exhibition catalogue, co-curators Kathryn Smith and Roger van Wyk describe DADA as having a lively history within Africa. DADA is presented as an artistic potential in the resistance against the apartheid regime and against neo-colonial dynamics in Africa. The exhibition showed original DADA artworks that were, however, placed in a current context so as not to present the connection between Europe and Africa as a one-sided affair. Why this idea was not taken up again for the current exhibition in Berlin remains open.

Africa is not merely a projection surface, as displayed in the exhibition, but, as Tristan Tzara once wrote, also a continent of the future. The Berlinische Galerie has passed up the chance to prove this.

.

DADA Afrika – Dialog mit dem Fremden, August 5 – November 7, 2016, Berlinische Galerie, Berlin.

.

Spunk Seipel is based in Berlin and Vrane nad Vlatvou. He studied Art History and Business Studies in Berlin and Vienna. Seipel has worked as a curator among others in Berlin, Prag, Bukarest, London, Johannesburg, Harare, Cape Town and Windhoek.

More Editorial