Malawi-born, London-based conceptual artist Samson Kambalu on the aesthetic spirit of play at this year’s 56th edition of the Venice Biennale.

Samson Kambalu

Malawi-born, London-based conceptual artist Samson Kambalu on the aesthetic spirit of play at this year’s Venice Biennale.

Reviews for All the World’s Futures are mostly confused. Some say the show is too difficult to get into, others postulate that it lacks a center of gravity to draw everything together. It is perhaps too subtle and considered, but there is a clear entry into it – by way of the Arena. “Bwalo,” we call it in Chichewa – a place of prodigious expenditure.

The Arena is where all aspects of culture, both good and bad, are represented to the public as universal poetry: “Gule Wamkulu,” the Great Play. Okwui Enwezor is the orchestrator of what he has called a “parliament of forms,” All the World’s Futures. He turns Venice into “mzinda,” the place of the Arena. Here multitudes are gathered from all over the world, bearing gifts and grievances.

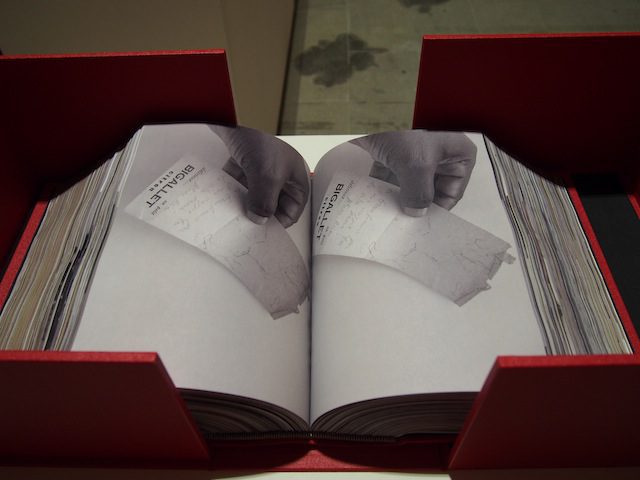

At the Venice Biennale 2015 © Samson Kambalu

My work is “nyau,” that is to say that play is central to its aesthetic conception. The Dutch historian Huizinga, in Homo Ludens, traces various aspects of culture outside the world of work as originating from play, whether in politics, religion, law, or academia. Play is what moves society. When play has ossified into an institution, society loses its essential vitality. The Arena is where aspects of culture are once more revealed and revitalized through creative play, “nyau.” This is what is happening in Enwezor’s All the World’s Futures.

In a globalized world, where social, economic, and political urgencies risk immediate commodification upon their conception, Enwezor’s Biennale, the Arena, offers an anti-reification sanctuary. This starts with Marx, the arch-critic of the system of reification, whose sanctioned Capital is rejuvenated here and gifted as literary drama. Within the Arena, Marx is not to be studied, but employed as a catalyst for a universal celebration of culture, the Great Play. It is in this way that we are to read the various contributions from African artists.

I am contributing three projects to the Biennale: “The Last Judgement,” 400 soccer balls plastered with pages of the Bible; “Sanguinetti Breakout Area,” a détourned representation of the Italian Situationist’s papers that were recently bought by Yale University; and “Nyau Cinema (Hysteresis),” an African version of early cinema built around the values of play. All these works were conceived with the Arena in mind. These works are socially and politically minded, but their success or failure can only be determined within the realm of universal poetry.

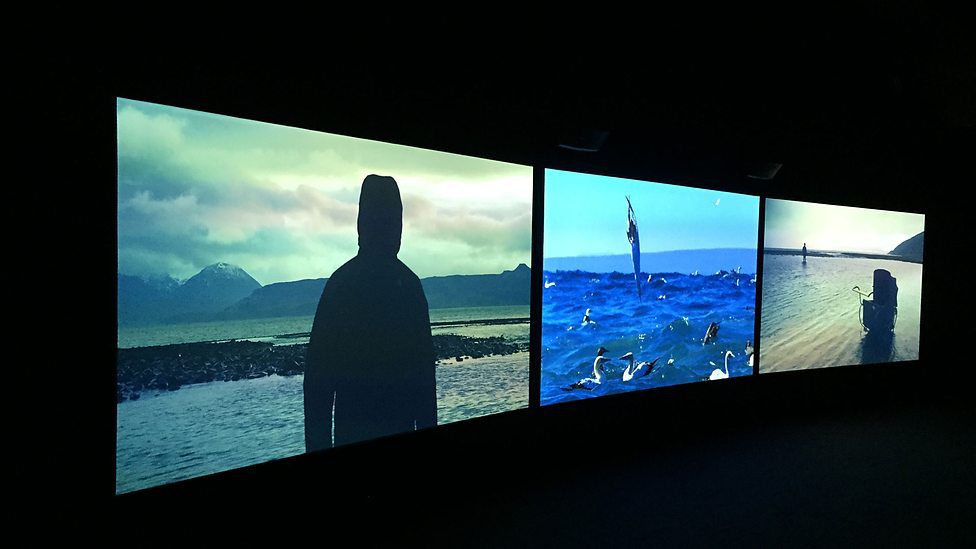

Source: BBC © Bill Thompson

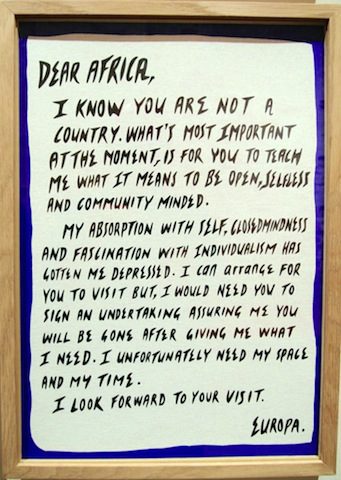

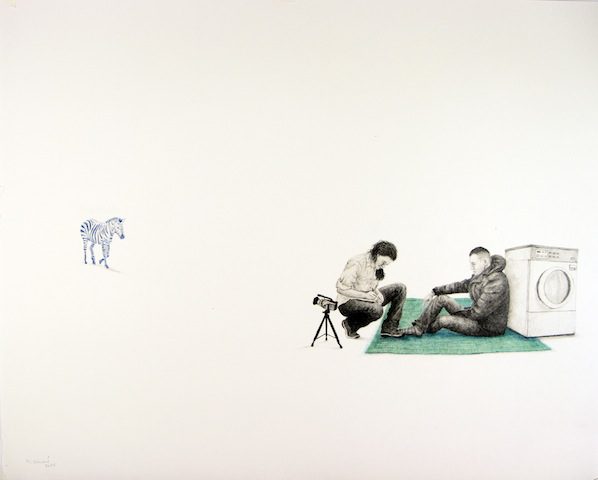

Walking through Barthélémy Toguo’s installation, it was the sacrificial orgy of his wooden torsos that drew your attention to the social concerns of his work. Marlene Dumas paints skulls, which viewed together constitute a Dance Macabre before a world marred by industrial violence. Gonçalo Mabunda’s utility art is animated by the superfluous ferocity of civil war. In John Akomfrah’s “Vertigo Sea,” transience is an inalienable aspect of exuberant beauty. Karo Akpokiere presents an exposition of transnational social concerns, which find their communication in graphic witticism. For Massinissa Selmani, drawing is where the thin line between tragedy and comedy in the social space can be revealed.

© Karo Akpokiere

According to All the World’s Futures, the world is a complicated and bleak place, but this only serves to highlight the Great Play’s urgency in the age of globalization. Dostoevsky said, “Beauty will save the world”: in the Arena, it is play that will save the world.

Massinissa Selmani, Do we need shadows to remember ? Graphite on paper, 40 x 50 cm, 2013-2014. Courtesy of the artist

This article is a reprint of a piece originally appeared in the June issue of Art in Culture, South Korea.

More Editorial