Life Performs Itself

14 February 2014

Magazine C& Magazine

7 min de lecture

Ray Daniels Okeugo, whom I worked with from 2011 until his untimely death in October 2013, was a photographer, actor, and, months before his passing, a movie producer. Most of his photographic oeuvre was produced during the course of his involvement with the Invisible Borders Trans-African Organization; he participated in four road trips from Lagos …

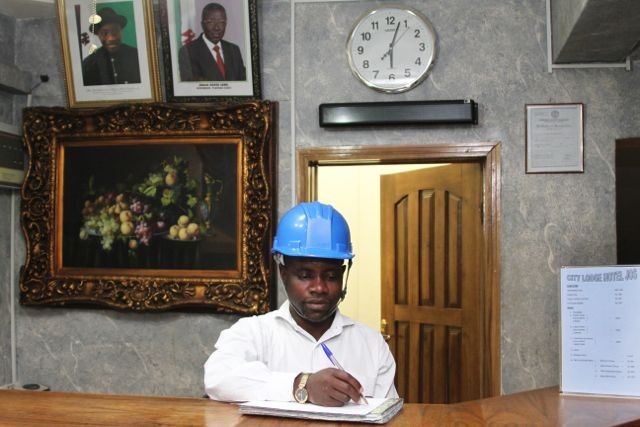

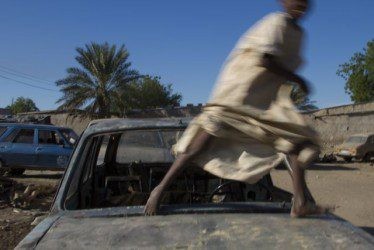

<div> Ray Daniels Okeugo, whom I worked with from 2011 until his untimely death in October 2013, was a photographer, actor, and, months before his passing, a movie producer. Most of his photographic oeuvre was produced during the course of his involvement with the Invisible Borders Trans-African Organization; he participated in four road trips from Lagos to other parts of Africa, and while travelling, he produced the photographs that we now contemplate. To put my immediate thought about his work forward, I find it necessary to account for how his photographs are resolute in their tender perceptiveness of the transient, which is the culminating effect of spending an average of five days in cities while on a road trip and producing work in motion.

To explain the aura in his photographs, I turn to the album cover of Bassekou Kouyate’s <i>Jama Ko</i>. Three seated men are holding an <i>ngoni</i> while a woman is standing with a microphone reclining on the window frame. All smiles, the band members seem to be at a rehearsal. I imagine the photographer stood at the edge of the moment, with extreme patience, knowing there was a lingering grace that would inescapably come into view. The photographer must have known that life would perform itself; he only had to be attentive. We see that this patience, which readies him on the edge of a photograph about to be made, also opens up a view of an alacritous happening. It is the same sort of readiness I find in the photographs of Okeugo.

Born in 1980 in Aba, southeastern Nigeria, Okeugo actively became involved with photography in 2007, closely working and assisting his childhood friend Emeka Okereke. Having only studied up to secondary school level, he compensated for this by attending numerous workshops, master classes, and exchange projects. Okereke was a strong influence—both photographers share an inclination to capture the frenzy and humour of the streets. And while he produced photographs, Okeugo acted in Nigerian soap operas and motion pictures, thus confirming his flair for photographing fleeting narratives. By working with and learning from other acclaimed Nigerian photographers— Akinbode Akinbiyi, Uche James Iroha, Amaize Ojeikere, Charles Okereke, Uche Okpa Iroha—Ray Daniels acquired a distinctive taste.

I recall that he always seemed to see the cracks in the surface of an occurrence. We must bear in mind that time and again he found a pose in moving people and things, poses laced with joviality. His photographs are marks of an onlooker who did not judge the absurdities of life in African countries. If anything, his photographic eye sought out these unobserved absurdities, framing them with a genuine kindness, hence warding off the criticism that his was a condescending gaze—and this would have been impossible had he not been the kind of person he was. A recurrent quality people remembered after his sudden death was his willingness to give himself to the service of his friends and colleagues, selfless “in a pure sense”, as Okereke wrote me in an email.

John Berger, in his dispatches about place (Hold Everything Dear), points us to the “specific gravity” of a destination. Taken as a parable about distance, it could also suffice as the story of a visitor who has arrived at a place that is ultimately not his destination. Upon arrival, the travelling visitor has to discover for himself the specific gravity of that destination, what troubles the place, and the marks of humour and despair that attend it. Berger’s parable ends:

“Sometimes a few of these travellers undertake a private journey and find a place they wished to reach, which is often harsher than they foresaw, although they discover it with boundless relief… They accept the signs they follow and it’s as if they don’t travel, as if they remain where they already are.”

Okeugo was not the kind of photographer who struggled to shed his alien feathers. Upon arrival at a place, he seemed to forcefully reject the identity of a stranger in order to become the kind of visitor who could be mistaken as a resident. During his travels he took photographs of Igbo businessmen in Chad and Libreville, framing them within their workspaces, spending time with them. I suppose that in the time he spent with them, his camera was not at the epicentre of their conversation. It was a casual tool that was used at the time of departure, like when you visit an old friend and it becomes inevitable that one creates memorabilia of the visit. His gaze was unflinching. He appeared poised to track an imaginary line drawn across the continent. If there is any ideological statement in his photographs it is the idea that everywhere you turn life is performing itself.

<a href="http://3.230.254.106/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Local-boy.-Gamboru1-374x250.jpg">

Emmanuel Iduma trained as a Lawyer in Nigeria and is the author of Farad, a novel. He is studying in New York.

</div>